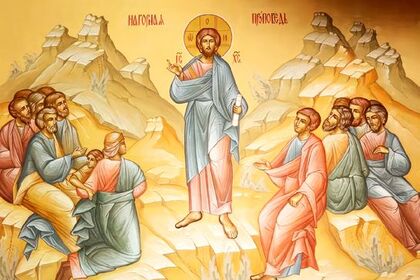

The spiritual evening in the month of October began exploring the Beatitudes, eight in number, which the Lord delivered at the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount. The most spiritual and complete text of the Beatitudes is in the Gospel of the Holy Evangelist Matthew, chapter 5, verses 1-12, and the more basic version is in the Gospel of the Holy Evangelist Luke, chapter 6, verses 20-23.

The spiritual evening in the month of October began exploring the Beatitudes, eight in number, which the Lord delivered at the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount. The most spiritual and complete text of the Beatitudes is in the Gospel of the Holy Evangelist Matthew, chapter 5, verses 1-12, and the more basic version is in the Gospel of the Holy Evangelist Luke, chapter 6, verses 20-23.

The Beatitudes are the beginning of the Lord’s Sermon on the Mount, which represents, in essence, the fullness of His teachings and commandments. Ultimately, the Lord’s commandments are an invitation to divine beatitude or blessedness, not to human happiness. They are beatitudes if viewed from the perspective of the Heavenly Kingdom. But from the worldly perspective, they are recipes for misery.

Father Constantin Coman says: “We no longer deal with imperative expressions, but rather with declarative statements that reveal or punctuate a certain inner state of man that is compatible with the Heavenly Kingdom… The second half of each beatitude is not a reward, but a natural outcome of the state mentioned in the first half: Those poor in spirit inherit, due to their inner state, the Heavenly Kingdom, which is not a place, but more accurately a condition. Poverty in spirit, together with the other conditions, are compatible with the Kingdom.”

The Beatitudes represent a ladder of spiritual ascent which our Lord invites us to climb. Saint Gregory of Nyssa says the same: “In the listing of the eight Beatitudes, we ascend them like stairs. The listing shows in words how, by ascending the steps one by one, the ascent is made easier. Because the one who has sensibly reached the first Beatitude, through an auto-development of meaning, awaits the next one too.”

Saint Symeon the New Theologian explains the organic character of the Beatitudes: “May we desire with all our soul to embrace God’s commandments: spiritual poverty, which the Word calls humility, unceasing tears day and night, from which spring forth spiritual joy and the hourly comfort of those who love God.” And he explains further: “Because being refreshed constantly and fattened with tears and completely quenching through them his irascibility, man becomes meek and gentle and completely unmoved by anger, but craves and desires with hunger and thirst (Matthew 5.6) to learn the statutes of God (Psalm 118.71). But in these conditions, he becomes merciful (Matthew 5.7) and compassionate, such that as a result, his heart becomes perfected and attains to vision of God, seeing purely (Matthew 5.8) His glory in accordance with His promises. Therefore, those who possess such souls are truly peacemakers and are called sons of the Most High (Matthew 5.9; Psalm 81.6), who know purely their Father and Master, and love Him with all their soul, enduring patiently for His sake all hardships and misfortunes, being reproached, slandered, straitened for His righteous commandment, which He commanded us to keep, being insulted and persecuted and enduring joyfully every word uttered in a false manner against them for His name, rejoicing (Matthew 5.11-12) that they were deemed worthy to be dishonored by men for His love (Acts 5.41).”

The first beatitude is “poverty of spirit,” which, at least in the Romanian milieu, suffered from a totally deformed understanding among the common people. In fact, as a Protestant commentator observes, “poverty of spirit” refers to those people who perceive in their conscience that they are in a deplorable and unhappy state, they perceive within themselves the opposite of having plenty, a condition of moral poverty and helplessness is familiar to them. And the example par excellence is the publican in the Gospel. Another (Anglican) commentator identifies this state with those people who, within themselves, consider themselves to have nothing of their own, they need to receive in order to give, they are dependent on the wealth of others.

Saint John Chrysostom says that the “poor in spirit” are “those who are humble, whose heart is contrite, who willingly humble themselves and play themselves down.”

Father Zacharias Zacharou gives the best interpretation of this beatitude and shows how it is organically linked to the second one: “If we see the beatitudes in Matthew’s Gospel as a summary of the entire Gospel, these beatitudes represent a ladder that ascends from earth to heaven, and the foundation of the beatitudes is coming to know my spiritual poverty, because the first beatitude says: ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit.’ When, in the heat of repentance, we come to know our spiritual poverty, then we will surely lament because of it. And spiritual weeping brings divine consolation.”

Thus, the second beatitude follows organically from the first. Saint Gregory of Nyssa says: “I reckon that the Word does not praise tears, but rather the knowledge of good, which follows from suffering the sadness that one’s life lacks that which is desired. […] And consolation springs forth from communion with the Comforter, for the grace of consolation is a work of the Spirit.” And Saint John Chrysostom explains: “In this beatitude, Christ did not speak generally about those who cry for any of various motives, but about those who weep for their sins. Christ calls blessed those who mourn after God. He commands us to weep not only for our sins, but also for the sins of others. The souls of the saints had this character: such was the soul of Moses, of Paul, of David!”