Biruind gândul ce-i venea de-a o rupe la fugă, el deschise ușa odăii bolnavului. Năprasnică duhoare de hoit și de privată. Ochii săi, înțepați de țipirig, se închiseră, lăsându-i de-abia vremea să vadă de pe la spate, o tigvă lustruită ca o bășică umflată, precum și un braț, cu pielea pe os, ce atârna pe marginea patului plin de țoale scârnave.

Adrian se lăsă în genunchi și își lipi fruntea de mâna asta de schelet, rece ca gheața. Bolnavul nu se mișcă.

- Ridică-te... Adriene... Și îndură-mă...

Adrian se înfioră. Nu era o voce de om, graiul bărbătesc al lui Anghel, ci o miorlăitură ieșită din nasul unui copil murind de oftică.

El se ridică cu pălăria în mână și stătu drept, smerit, în mijlocul odăii, în fața bolnavului. Bolnavul acesta nu era unchiul său Anghel, ci un moșneag cu obraz de mumie; cu ochi mari, strălucitori, lipsiți de pleoape și scufundați în două orbite goale; cu nasul lungit și subțiat ca un vârf de cuțit, cu buzele fripte și cu gura întredeschisă. O cunună de peri albi înconjura ceafa de la o tâmplă la alta. Barba, creață și neagră pe vremuri, nu mai era decât o învălmășeală de câlți fumurii. Împreună cu cele două brațe de schelet care se bălăbăneau în mânecile cămășii, era tot ce se vedea apărând dintr-o grămadă de saci, velințe și ghebe rupte. Era tot ce rămăsese din moș Anghel.

[…]

Nu mai sufăr deloc.. .Capul singur mai trăiește... Restul... nu-l mai simt. S-a sfârșit cu... restul. Dar capul!... Ce minunat lucru!

Anghel tăcu un moment, și privi țintă la nepotu-său; apoi, cu încredințare:

- Trebuia să mor de-acum trei zile... fiindcă nu mai aveam nimic de cugetat, când Irimia veni spre seară să-mi spună că te-ai întors... Atunci am mai zăbovit, așteptându-te...

[…]

Anghel se opri un moment ca să răsufle. Adrian crezu că se află în fața unuia din acei faraoni îmbălsămați, din muzeul „Bulac”, din Cairo, un faraon ai cărui ochi redeschiși nu mai clipeau. Pielea obrazului, mișcătoare, uscată, străvăzătoare, lăsa să se vadă toate oasele feței deasupra cărora aluneca, întinsă ca o foaie subțire de pergament, amenințând parcă să se rupă la fiece mișcare.

[…]

De trei ani de zile, n-am mai pus piciorul jos din patul în care mă vezi. Trei ierni, trei primăveri, tot atâtea veri și tot atâtea toamne de când stau culcat pe spate și mă uit la tavanul ăsta înnegrit. E vremea cea mai puternic trăită din toată viața mea. De-un an nu mai mănânc și nu mai dorm aproape deloc, iar de șase luni încoace, deloc, deloc; nici o fărâmitură de pâine, nici o clipă de somn. În schimb, beau, beau rachiul ăsta. Ziua, băiatul mi-l varsă pe gât, după cum văzuși. Noaptea, ca să nu pier și ca să nu scol din somn pe sărmana ființă, sug buretele ăla de pe masă, pe care îl îmbibez cu rachiu. Dimineața e uscat ca iasca, ars de buzele mele...

Adrian își acoperi fața cu mâinile:

- Vai, unchiule, strigă el, ce groaznică viață!...

- Groaznică, zici tu, nepoate? Groaznică? O fi... Dar e dreaptă, potrivită soartei mele... Am voit fericirea întreagă, fericirea ușuratică, îndestularea cărnii deșarte... Și ca s-o am, m-am zbătut aprig. Douăzeci de ani de luptă, pentru ca să dobândesc o femeie frumoasă, care adoarme mâncând; acareturi înfumurate, cari ard ca paiele; vite, cari dispar; copii, cari mor; aur, care-ți aduce lovituri de măciucă; o cămașă curată, care e murdară a doua zi. Toate astea trebuincioase unui trup care s-a desprins de capul meu, care mi-e tot așa de străin ca și boarfele care-l acopăr, trupul ăsta care putrezește acuma, care nu mai e decât un hoit!... Am petrecut o viață de om, un sfert de veac, sclav al acestei putreziciuni, pe care aș vrea s-o văd mâncată de corbi, așa cum e în clipa de față roasă de viermi. Un sfert de veac... Și nici într-un moment n-am băgat de seamă că aveam un cap, un creier, o lumină pe care putregaiul și viermii nu pot s-o atingă.

Înăbușit de sforțarea făcută, bolnavul tăcu câtva timp. Adrian, îndurându-i cu greu privirea, se întreba dacă nu cumva unchiul său avea să-i facă vreo mustrare. Chiar așa era;

- Adriene!... Te-am chemat ca să-ți spun că sunt nemulțumit de tine!..

Biciuit, tânărul tresări:

- Nemulțumit de mine, unchiule?!... Și de ce?

- Fiindcă ești un desfrânat!... Fiindcă uiți lumina din capul tău și cuvintele mele de altădată!... Asta e îngăduit multor mii de oameni de rând, ca mine, dar nu ție. Adriene, m-auzi? Nu ție! Creierul tău a cunoscut lumina din cea mai fragedă copilărie.

[…]

Dar, hait!... Departe, departe de mine, aste cumplite amintiri!.. . Iar tu, Adriene, nepoate, tu trebuie să mă asculți, tu îmi datorești supunere! Tu nu trebuie nimic să nădăjduiești, nimic să aștepți de la viața care zdrobește pe om, care putrezește trupul și te face să uiți că ai un cap.

Ce înseamnă nerușinarea asta pe tine?... Ce e îmbrăcămintea asta făcută pe măsură?... Ce e gulerul ăsta înfumurat?... Ce sunt manșetele astea strălucitoare?... Ce?... Îi trebuie toate aceste împopoțoneli unui tânăr care cunoaște lumina cerului și știe ce-a pățit unchiul său Anghel?...

[…]

- Iartă-mă!... iartă-mă... sunt un ticălos!.. .

- Foarte bine!... Te căiești!... Și căința aduce îndreptarea. Silește-te să te-ndrepți, și te iert de pe-acuma; și ai să fii Adrian al meu, nepotul meu, fiul de suflet al lui moș Anghel, al ăstui moș Anghel ce-l vezi putrezind pe țoalele astea, din greșeala de-a fi voit nevasta prea frumoasă, casa prea înfloritoare și cămașa prea curată. Dar basta!

(va urma)

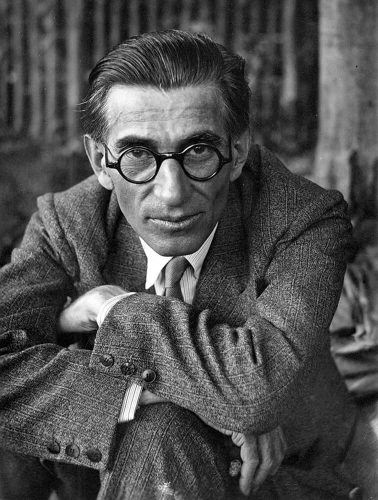

Panait Istrati