Long ago I tore my spirit from the world and mingled it with the shining spirits of heaven. The lofty mind bore me far from the flesh, set me in that place, and hid me in the recesses of the heavenly abode. There the light of the Trinity shone upon my eyes, a light than which I have known nothing brighter. It is throned on high and gives off an ineffable and harmonious radiance, which is the principle of all those things that time shuts off from heaven.

Long ago I tore my spirit from the world and mingled it with the shining spirits of heaven. The lofty mind bore me far from the flesh, set me in that place, and hid me in the recesses of the heavenly abode. There the light of the Trinity shone upon my eyes, a light than which I have known nothing brighter. It is throned on high and gives off an ineffable and harmonious radiance, which is the principle of all those things that time shuts off from heaven.

I died to the world and the world to me, and I am become a living corpse as devoid of strength as a dreamer. Since that day my life is elsewhere; but I groan under the yoke of the crass flesh, which wise men have called the darkness of the mind.

When released from this life and this impeded vision, from men who crawl on earth, wander and make to wander, I greatly long to have a purer vision of the stable things. Then, not as formerly, they will be unadulterated by association with obscure images which can set the vision of the keenest mind astray. With the eye of a mind made pure I shall gaze upon truth itself. But all that is still to be.

Things here below amount to sordid smoke or dust for those who have exchanged this life for the great life, the earthly for the heavenly, the destructible for the stable. Consequently I am set upon by all. They refuse to give way, and rush upon a quarry that is all too easy.

[…] It is my soul that I lament, as one would mourn a queen, fair, and stately, and sprung from a noble line of kings, that he might see languishing, fast in chains, when enemies have taken her with the spear. They have bound her in harsh slavery, and she bends her sad gaze upon the ground. For such was my fate. In such wise am I stricken to the heart.

Folklore has it that when the bitter serpent has sunk his malicious fang into someone, that man will reveal the pestilent sore only to those who have been likewise wounded by the same hateful creature’s feverish venom. They alone can appreciate its grievous character. So with me. I shall recount my woe to people united with me by love, or misfortune, or similar pain, because they alone could hear the tale with sympathy. They are capable of insight into the mysteries of a laden heart, who yearn to take upon their shoulders the burden of the cross, who have their portion in the fold of the great King, who love the path of rectitude and treat the fallen with compassion.

As for others, the recital of my woes might well seem ridiculous to them. They are the people whose heart has been touched only superficially by the faith, who have never known in their inmost being the sharp stab of desire for the King. Their abode is here below, their concern only for ephemeral things. Upon this they whet the ready weapon of their tongue against everyone alike, be he good or evil. As for me, I shall not give over my laments until I make good my escape from lamentable evil, and place a padlock on the mad passions of the mind. Satan, the evil one, has thrown open all the doors to them, doors that were fast before, when I was sheltered by the hand of God. In those days evil could not approach me, but it is swift to gain a hold. When a reed comes close to a fierce blaze it catches fire, and the wind sends the flame on high.

Would to God I had hidden myself in cliffs, and mountains, and crags, before all this came about. Fleeing this world, this way of life and the anxieties of the flesh, I could have filled my mind totally with Christ. I could have lived apart from others, elevating a pure spirit to God alone until the day when, in buoyant hope, I should attain my final goal. Would to God indeed. But I was overwhelmed by affection for my dear parents, and dragged earthwards by that weight. Not so much affection indeed, but pity, the tenderest of all emotions, which penetrates to the marrow of one’s being. Pity for the grey hairs that were godlike, pity for their pain, their childlessness, pity too because of their child. Their tremors are for him, as they surround him, the apple of their eye, the sharer of their agonies, with tender care.

Previously, books were his whole preoccupation, the books the Spirit had made by the tongues of his holy ones. Within was the shining grace of the Spirit’s noble composition, the concealed treasure which is manifested only to the pure among mortals. Prayers and groans were dear to him, and sleepless nights, and the angelic choirs who stand and beseech God in psalms, elevate their souls to God in hymns while they harmonize many mouths into a single voice. Dear to him, too, the distress of that fount of evil, the belly, and moderation in laughter, control of tongue and eye, and rein on furious anger. That wanderer, the mind, which peers about everywhere, reason would keep in check. He directed it to Christ in heavenly hopes. With reason presiding over everything, leading the image to the King, God found the zealous effort pleasing.

Previously, books were his whole preoccupation, the books the Spirit had made by the tongues of his holy ones. Within was the shining grace of the Spirit’s noble composition, the concealed treasure which is manifested only to the pure among mortals. Prayers and groans were dear to him, and sleepless nights, and the angelic choirs who stand and beseech God in psalms, elevate their souls to God in hymns while they harmonize many mouths into a single voice. Dear to him, too, the distress of that fount of evil, the belly, and moderation in laughter, control of tongue and eye, and rein on furious anger. That wanderer, the mind, which peers about everywhere, reason would keep in check. He directed it to Christ in heavenly hopes. With reason presiding over everything, leading the image to the King, God found the zealous effort pleasing.

The phantasms of the night simply reproduce one’s daily preoccupations; and for me possessions and strident clamors mean bad dreams by night. Their place was taken previously by the splendor of God, which blinded my vision, by the illustrious chorus and the glory of pious souls. As it is, all such treasures have vanished from a soul that once enjoyed only the company of the best.

All I have now is yearning and the hopeless pain. Hence these tears. What the morrow will bring I do not know. Will God deliver me from my woes, shake all anxieties away, and lead me again to former ways? Or will He drive me hence in the midst of my anxieties before I can see the dawn, before I can lay a salve to my wounds? After the depths of the night behold me thirsting for the light. Is there any succour for vain laments? In the place where mortals have their remedy, all decisions are irrevocable. Grey hairs are already upon me, and my wrinkled limbs tend towards the evening of this life of tears.

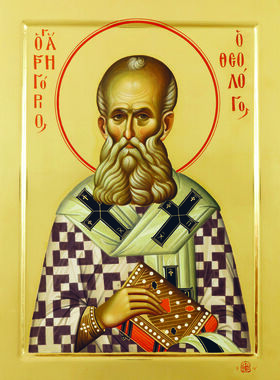

St. Gregory the Theologian, excerpt from “Concerning his own affairs”

in Three Poems, trans. Denis Molaise Meehan (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University Press, 2001), pp. 31–35.