…Fire, fire! The branches crackle and the night wind of late autumn blows the flame of the bonfire back and forth. The compound is dark; I am alone at the bonfire, and I can bring it still more carpenters’ shavings. The compound here is a privileged one, so privileged that it is almost as if I were out in freedom—this is an Island of Paradise; this is the Marfino “sharashka”—a scientific institute staffed with prisoners—in its most privileged period. No one is overseeing me, calling me to a cell, chasing me away from the bonfire. I am wrapped in a padded jacket, and even then it is chilly in the penetrating wind.

…Fire, fire! The branches crackle and the night wind of late autumn blows the flame of the bonfire back and forth. The compound is dark; I am alone at the bonfire, and I can bring it still more carpenters’ shavings. The compound here is a privileged one, so privileged that it is almost as if I were out in freedom—this is an Island of Paradise; this is the Marfino “sharashka”—a scientific institute staffed with prisoners—in its most privileged period. No one is overseeing me, calling me to a cell, chasing me away from the bonfire. I am wrapped in a padded jacket, and even then it is chilly in the penetrating wind.

But she—who has already been standing in the wind for hours, her arms straight down, her head drooping, weeping, then growing numb and still. And then again she begs piteously: “Citizen Chief! Forgive me! Please forgive me! I won’t do it again.”

The wind carries her moan to me, just as if she were moaning next to my ear. The citizen chief at the gatehouse fires up his stove and does not answer.

This was the gatehouse of the camp next door to us, from which workers came into our compound to lay water pipes and to repair the old ramshackle seminary building. Across from me, beyond the artfully intertwined, many-stranded barbed-wire barricade and two steps away from the gatehouse, beneath a bright lantern, stood the punished girl, head hanging, the wind tugging at her gray work skirt, her feet growing numb from the cold, a thin scarf over her head. It had been warm during the day, when they had been digging a ditch on our territory. And another girl, slipping down into a ravine, had crawled her way to the Vladykino Highway and escaped. The guard had bungled. And Moscow city buses ran right along the highway. When they caught on, it was too late to catch her. They raised the alarm. A mean, dark major arrived and shouted that if they failed to catch the fugitive girl, the entire camp would be deprived of visits and parcels for a whole month because of her escape. And the women brigadiers went into a rage, and they were all shouting, one of them in particular, who kept viciously rolling her eyes: “Oh, I hope they catch her, the b***h! I hope they take scissors and—clip, clip—take off all her hair in front of the line-up!” (This wasn’t something she had thought up herself. This was the way they punished women in Gulag.) But the girl who was now standing outside the gatehouse in the cold had sighed and said instead: “At least she can have a good time out in freedom for all of us!” The jailer overheard what she said, and now she was being punished; everyone else had been taken off to the camp, but she had been set outside there to stand “at attention” in front of the gatehouse. This had been at 6 P.M. and it was now 11 P.M. She tried to shift from one foot to another, but the guard stuck out his head and shouted: “Stand at attention, w***e, or else it will be worse for you!” And now she was not moving, only weeping: “Forgive me, Citizen Chief! Let me into the camp, I won’t do it any more!”

This was the gatehouse of the camp next door to us, from which workers came into our compound to lay water pipes and to repair the old ramshackle seminary building. Across from me, beyond the artfully intertwined, many-stranded barbed-wire barricade and two steps away from the gatehouse, beneath a bright lantern, stood the punished girl, head hanging, the wind tugging at her gray work skirt, her feet growing numb from the cold, a thin scarf over her head. It had been warm during the day, when they had been digging a ditch on our territory. And another girl, slipping down into a ravine, had crawled her way to the Vladykino Highway and escaped. The guard had bungled. And Moscow city buses ran right along the highway. When they caught on, it was too late to catch her. They raised the alarm. A mean, dark major arrived and shouted that if they failed to catch the fugitive girl, the entire camp would be deprived of visits and parcels for a whole month because of her escape. And the women brigadiers went into a rage, and they were all shouting, one of them in particular, who kept viciously rolling her eyes: “Oh, I hope they catch her, the b***h! I hope they take scissors and—clip, clip—take off all her hair in front of the line-up!” (This wasn’t something she had thought up herself. This was the way they punished women in Gulag.) But the girl who was now standing outside the gatehouse in the cold had sighed and said instead: “At least she can have a good time out in freedom for all of us!” The jailer overheard what she said, and now she was being punished; everyone else had been taken off to the camp, but she had been set outside there to stand “at attention” in front of the gatehouse. This had been at 6 P.M. and it was now 11 P.M. She tried to shift from one foot to another, but the guard stuck out his head and shouted: “Stand at attention, w***e, or else it will be worse for you!” And now she was not moving, only weeping: “Forgive me, Citizen Chief! Let me into the camp, I won’t do it any more!”

But even in the camp no one was about to say to her: All right, idiot! Come on in!

The reason they were keeping her out there so long was that the next day was Sunday and she would not be needed for work.

Such a straw-blond, naive, uneducated slip of a girl! She had been imprisoned for some spool of thread. What a dangerous thought you expressed there, little sister! They want to teach you a lesson for the rest of your life.

Fire, fire! We fought the war—and we looked into the bonfires to see what kind of a Victory it would be. The wind wafted a glowing husk from the bonfire.

To that flame and to you, girl, I promise: the whole wide world will read about you.

This was happening at the end of 1947, a few days before the thirtieth anniversary of the October Revolution, in our capital city of Moscow, which had just celebrated eight hundred years of its cruelties. Little more than a mile away from the All-Union Agricultural Fair Grounds. And a half-mile away from the Ostankino Museum of Serf Arts and Handicrafts.

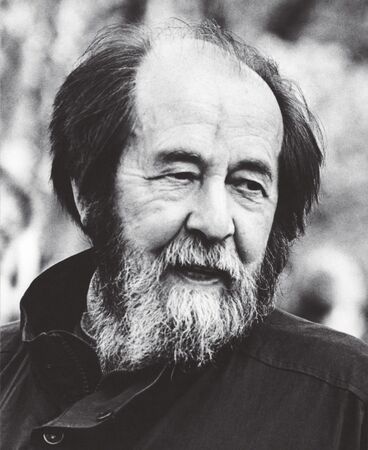

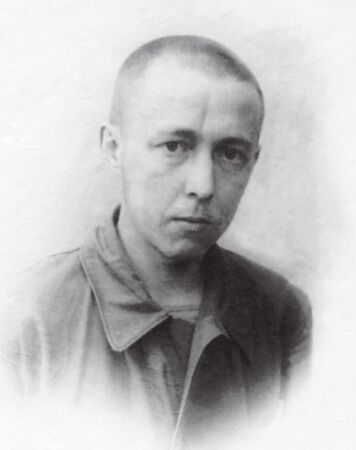

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Extract from The Gulag Archipelago, Part III, Chapter 5