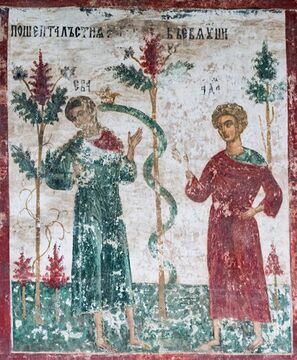

Among mortals two gates towards hateful death are open. There are those who develop in their mind a turbid spring of evil. They are always concerned with presumptuous deeds, with the body, with wanton satiety, with hateful intrigues. They drive themselves to every transgression, rejoice in evil, love their own doom. The others behold God with the pure eye of the mind. They hate pride which is the shameless offspring of the world. Far from the contaminations of the world they take their course, their flesh wasted to a shadow. Their tread upon the earth is lighter, for they are buoyed up by the Spirit as they follow the God who calls them. Mystics of the hidden life of Christ the King, they go forward in the hope of shining one day for all eternity with the brilliance of that life.

Among mortals two gates towards hateful death are open. There are those who develop in their mind a turbid spring of evil. They are always concerned with presumptuous deeds, with the body, with wanton satiety, with hateful intrigues. They drive themselves to every transgression, rejoice in evil, love their own doom. The others behold God with the pure eye of the mind. They hate pride which is the shameless offspring of the world. Far from the contaminations of the world they take their course, their flesh wasted to a shadow. Their tread upon the earth is lighter, for they are buoyed up by the Spirit as they follow the God who calls them. Mystics of the hidden life of Christ the King, they go forward in the hope of shining one day for all eternity with the brilliance of that life.

Nevertheless, in the inexorable scheme of things, they are tried by the evil thorns of living. The raging demon, the contriver of evil, devises from without a thousand stings of doom. Alas for mortals in their misery. Worsted in open conflict, the demon often hides hateful destruction under noble guise. He wreaks such havoc against human beings as does the bronze under the bait, which brings destruction to the fish. Seeking for life they draw the unforeseen bane into their entrails, and swallow their own doom. So it was with me. After I discovered the dark character of the evil one, he came at me in fair guise, like unto light. He would have me in my search for light draw nigh to wickedness, my fickle mind being filched away to its destruction.

Marriage, that channel of life, the greatest bond that matter has forged for human kind, never bound me. The soft weave of silk did not ensnare me. I took no pleasure in the luxuries of the table, in catering to an insatiable belly which is the wanton mother of lust. Living in great and brilliant houses did not please me, nor soothing my spirit with the tender strains of music. I was never surrounded by the soft effeminate scent of myrrh. Others could have their gold and silver: their passion to be surrounded by innumerable possessions brings them sparse satisfaction and much trouble. Plain fare is my delight, coarse food I find sweet, and salt and a meagre board, and with it all a fasting draught of water. Such, with Christ who ever elevates my mind, is my best wealth: no tracts of fertile land, no fair groves, no herds of kine, no flocks of fat sheep. Nor yet devoted slaves, my own race who have been separated from me by an ancient tyranny. To people sprung from one land it gave the double name of freemen and slave. Nay, not from one land, from one God. And so came into being this sinful distinction.

Human respect, soon evanescent like the wind, never woke need in me, nor glory that is doomed to perish. I did not seek to hold high place in the royal court: I was not consumed by ambition for distinguished seats of justice where I might don haughty airs on a lofty perch. Nor did I covet great influence in the state or among citizens, or take any joy in such vain and feeble dreams, that flutter this way and that and always vanish. Not for me the task of trying to embrace the onrushing river, clasping shadows in my hand, groping after mist. Such are the generations of mortals, such is prosperity, as slight as the wake the ship leaves behind, perceptible for a while but then dissolving into nothing.

The fame that goes with letters was the only thing that absorbed me. East and West combined to procure me that, and Athens, the glory of Greece. I labored much for a long time in the craft of letters; but even these two I laid prostrate before the feet of Christ in subjection to the Word of the great God. It overshadows all the twisted, variegated products of the human mind.

Such dangers then, I managed to avoid. But I did not succeed in avoiding the deceitful hatred of the evil one. He makes ambush under seemingly benevolent guise. To all and sundry I shall candidly relate my mishap because thus one escapes the intrigues of the wily beast. In catering to my parents, who were reduced by hateful age and mourning, I thought, O Christ my King, I was doing something pleasing to you and in accordance with your laws. I was the only remaining child, a dubious hope, the barest flicker from a great lamp that was now no more. It is you who grant sons as helping strength to mortals, who set them like a staff to support trembling limbs. […] In caring for them and sheltering their feeble years I consoled myself with the hope that I was fulfilling the most important duty laid upon us by nature. But how true the saying is that for the wrongdoer the path is strewn with pitfalls. Because the good deed in my case merely gave rise to evil.

Such dangers then, I managed to avoid. But I did not succeed in avoiding the deceitful hatred of the evil one. He makes ambush under seemingly benevolent guise. To all and sundry I shall candidly relate my mishap because thus one escapes the intrigues of the wily beast. In catering to my parents, who were reduced by hateful age and mourning, I thought, O Christ my King, I was doing something pleasing to you and in accordance with your laws. I was the only remaining child, a dubious hope, the barest flicker from a great lamp that was now no more. It is you who grant sons as helping strength to mortals, who set them like a staff to support trembling limbs. […] In caring for them and sheltering their feeble years I consoled myself with the hope that I was fulfilling the most important duty laid upon us by nature. But how true the saying is that for the wrongdoer the path is strewn with pitfalls. Because the good deed in my case merely gave rise to evil.

Night and day my mind and members are consumed by a host of gnawing anxieties that drag me down from heaven to my mother earth. In the first place, to control servants—what a net of destruction. Harsh masters they always hate, but upright ones they shamelessly exploit. The former cannot make them mild, nor the latter docile: against both they breathe immoderate venom. Then the administration of property, […] and have the harsh rebuke of the collector dinning one’s ears. The taxes which property entails destroy all freedom and bind your lips with a fetter. Caught in the swirl of the teeming agora, involved in miserable suits before the seats of magistrates, listening to the clamor and counterclamor of litigants, getting implicated in knotty twists of law, your lot becomes one of trouble and conflict. Here the wicked are more successful than the good, the dispensers of the law being prone to bribery from either side. Any villain at all who has money becomes the best of fellows. Without the help of God no one can avoid fraud and malpractice in company like that. One has to flee precipitately letting the rascals have the lot, or have one’s better self sullied by their machinations. People who come near the evil blast of fire will display the grim evidences either of the fire or the smoke. (To be continued)

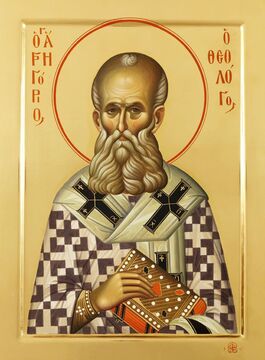

St. Gregory the Theologian

Excerpt from “Concerning his own affairs”

in Three Poems, trans. Denis Molaise Meehan (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University Press, 2001), pp. 26–30.